Tags: Comments Off on Bay Theatre Update

Bay Theatre Update

May 13th, 2009 by

Respond

New Life For The Franciscan Plaza

May 8th, 2009 by

Respond

Tags: 2 Comments

Hollywood’s Independence Day

May 7th, 2009 by

Respond

Tags: Comments Off on Hollywood’s Independence Day

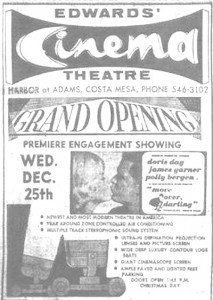

James Edwards II

April 27th, 2009 by

Respond

Tags: Comments Off on James Edwards II

San Juan Capistrano: Cinematic Trailblazer

April 16th, 2009 by

Respond

Tags: Comments Off on San Juan Capistrano: Cinematic Trailblazer

Last Exit

April 6th, 2009 by

Respond

Tags: Comments Off on Last Exit

Still Standing: The Brea Plaza

March 30th, 2009 by

Respond

Tags: 3 Comments

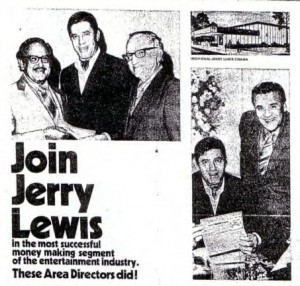

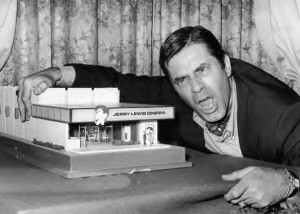

Fantasy & Failure With Jerry Lewis Cinemas

March 28th, 2009 by

Respond

Tags: 10 Comments

Escape To A Cool Movie

March 23rd, 2009 by

Respond

Prior to the 1920’s, movie going was more of a cool weather pastime, as the stuffy confines of theatre auditoriums didn’t particularly lend themselves to personal comfort during the summer months. With the arrival of hot weather, one was more likely to frequent the park or a ball game than the local cinema, sending box office receipts plummeting. Theatre operators attempted to overcome this issue through various gimmicks, such as the distribution of paper fans and free ice water (Anaheim’s Grand Theatre even advertised “perfumed” air, as a means of overcoming the unpleasantness that often accompanied an auditorium full of over-heated patrons), but the problem persisted until Willis Carrier introduced air conditioning to the industry in 1925.

First installed in New York City’s Rivoli Theatre, the new technology was initially met with skepticism, as movie goers attended a memorial day weekend test run with hand fans at the ready. However, by the end of the film, Paramount Pictures’ chief, Adolf Zukor, summed up the experience of air conditioning with, “Yes, the people are going to like it.” Within five years, Carrier had installed his system in an additional three hundred cinemas and the hot summer months had transformed in to the movie industry’s top grossing season.

Billed as everything from “refrigerated air” to “cool comfort”, air conditioning became a key marketing tool for cinemas, often appearing as prominently on marquees and in print advertisements as the features being shown. There might even be an argument made that air conditioning played a greater role in cinema’s mid twentieth century boom than the Hollywood machine that fueled the industry, as movie theatres stood as one of the few public outlets, that uniformly featured air conditioning, well in to the 1950’s.

While “AC” would begin to proliferate the urban landscape by the 60’s, becoming a standard feature in most businesses and even a common household amenity, cinemas remained a summer time staple. Even today, movie goers flock to theatres during the summer months; not only to escape in to a blockbuster film, but to escape from the heat in a “cool movie”.

Tags: Comments Off on Escape To A Cool Movie

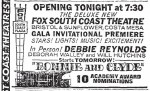

The Westwood of Orange County

March 17th, 2009 by

Respond

Tags: 3 Comments