In July of 1931, a theatre opened on Hollywood Boulevard with the bold prediction that it would “flame a revolution in film presentation.” Financially backed by business tycoon Howard Hughes, designed by renowned architect S. Charles Lee, and utilizing operations concepts which were decades ahead of their time, the theatre was among the first to openly challenge the grand movie palace ideal; perhaps, the first “modern” cinema, which predicted much of what awaited movie going in the latter half of the twentieth century. Yet, this theatre failed to flame any revolution, closing in less than a year and disappearing into historical obscurity. The Studio Theatre is the subject of our latest Forgotten Cinema.

The story of the Studio Theatre begins in late 1930, when Howard Hughes, fresh off the box office success of “Hell’s Angels”, sought to create his own cinema chain. Partnering with former Fox West Coast executive Harold B. Franklin, the two formally launched the Hughes-Franklin Company in January of 1931. Backed by Hughes’ immense wealth, the new circuit went on a nationwide buying and building spree, with plans to operate 200 to 300 theatres within two years. By March, Hughes-Franklin already owned 125 venues, in eight states, and had commissioned famed cinema architect, S. Charles Lee, to design a new run of theatres. Among the mostly traditional sites on Lee’s docket was one experimental theatre, which aimed to test a new course in film presentation.

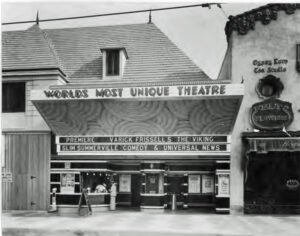

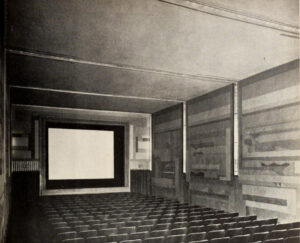

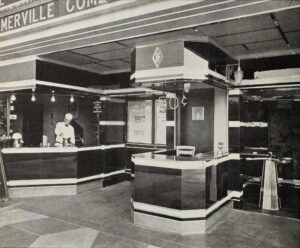

Located in the heart of Hollywood’s, then new, cinema epicenter, the Studio Theatre was promoted as the “world’s most unique theatre.” Intended as a counter to a perceived overindulgence, which had become the movie theatre standard of the day, the Studio was to place the focus “back on the pictures”. Forgoing the cavernous and opulent design of the nearby Egyptian and Chinese theatres, the Studio repurposed a retail property into an intimate 303 loge seat venue, with streamlined modern décor. Taking a que from Hughes’ interest in new technologies, the Studio featured automated sliding front doors (utilizing a pressure sensitive floormat), self-serve concession vending machines, a bill changing machine, and “whispering display cases” which provided film information via prerecorded messages. Additional “mechanical wonders” included a photobooth, automated drinking fountain (activated with an “electric eye” photocell), and an air-conditioning “weather factory” which was visible through a floor window.

While the assorted “world’s first” technologies may have been more marketing than innovation (several had already been introduced by the rival Trans-Lux chain), the true “revolutionary” and “unique” attributes of the Studio were found in the theatre’s efficiency. The streamlined facility design had allowed for the theatre to be built and opened in a matter of months, at a fraction of the cost seen with traditional cinemas (a design concept which also addressed the “white elephant” issue we covered in an earlier post). In turn, this design and the highly promoted automation technologies resulted in the Studio requiring as few as three people for operations (cashier, hostess, and projectionist), as opposed to the legions which had become standard practice elsewhere. Abandoning the prologs, intermissions, and stage shows of movie palaces, the Studio was able to schedule more daily screenings; aided further by the facility, which allowed for a quicker turnaround time between shows. Where even small-town movie houses regularly scheduled around extended gaps between shows, the Studio was purported to only be limited by the length of time it took audiences to exit/enter the auditorium. The theatre also included a work around for the “dead time” business lull during screenings, via a soda fountain which opened to the sidewalk, allowing for continuous concession sales. In general, the business model was based on cutting expenses and increasing revenue streams, through a focus on efficiency of operations; a seemingly standard practice by modern standards, but one which was unique in the era of over-the-top showmanship and grandeur.

While unintentional, a secondary “ahead of its’ time” feature could be found in the criticism the theatre faced from an assortment of industry and media figures. Dubbed as “classless” and the potential “death knell of cinema cathedrals”, there were those who felt the Studio’s approach to movie going cheapened the experience; believing the theatre harkened backwards to storefront nickelodeons, rather than advanced movies as a respectable art form. The glamour and prestige of the grand movie palace was being assaulted by a disposable, “for the masses”, cinema. All quite reminiscent of the chatter which surrounded the multi and mega plexes in the latter twentieth century.

Despite industry criticism, the Studio proved to be an instant hit with moviegoers. Unfortunately, the same couldn’t be said about the Hughes-Franklin circuit as a whole. Mistimed, during an industry downturn and the Great Depression, the chain had quickly turned into a money pit and Hughes sought to cut his losses. In January of 1932, the Hughes-Franklin Company announced that all holdings would be shuttered and/or sold “as soon as possible.” The Studio was later remodeled into a more traditional cinema and rotated through numerous operators over the ensuing fifty years; changing names from the Hollywood Music Hall, to Academy, and finally the Holly Theatre. In 1986, cinema operations ceased for good and the property was returned to retail use. Today, the site serves as the home of Harold’s Fried Chicken.

Tags: No Comments